Auditing with Rack Middleware

Rack

Rack describes itself as a “minimal, modular, and adaptable interface for developing web applications in Ruby”. In layman’s terms its just a set of rules that, when followed, allow web servers and web applications to talk to each other.

The typical flow of a web app is as follows:

- Web server receives request over the wire as plain-text

- Web server hands this request off to web application to do something

- Rails application takes some action, for example, updates a user record in the database

- Rails hands the response back to the web server

- Web server responds to the client as plain-text

Plain-text in, plain-text out.

There are lots of web servers: WEBrick, Thin, Puma, etc. There are even more Ruby web frameworks: Rails, Sinatra, Rum, Hanami, Merb, just to name a few.

One day web server authors and web framework authors got wise and held a big meeting. The web framework authors were growing really tired of having to write tons of code to support all the different ways web servers were handing them representations of these plain-text HTTP requests. Some passed a request as a raw String, others as an Array, and some gave it as a Hash - in Spanish! The web server authors were also getting pretty fed up with framework authors. Every framework was handing their responses to the web servers in a different format. Complete chaos. So what happened?

The web server peeps came up with a set of rules. They said your frameworks need to provide an app object that responds to the call method, taking a Hash representing the request.

This object needs to return an Array with three elements:

- HTTP response code

- Hash of headers

- the response body, which must respond to

each

And with that the seas parted and Rack was born.

Here’s a bare-bones rack app built from a Proc. Notice it follows all of the above rules.

require 'rack'

app = Proc.new do |env|

['200', {'Content-Type' => 'text/html'}, ['A barebones rack app.']]

end

Rack::Handler::WEBrick.run app

Not a week after Rack was released Medium and HackerNews exploded with posts about the Death of Rack. They thought Rack was great, but there were three problems:

- Developers needed the ability to manipulate requests after their web server had received them, but before they reached their web framework.

- They needed the option to manipulate responses after their web framework had responded, but before they reached their web server to be sent to the client.

- No keyboard warrior on either site could decide which color the logo should be.

Problem #3 was punted for a further date, but the Rack authors quickly came up with a solution to problems #1 and #2. They figured their solution would sit in the middle of the web server and the application and it needed to sound somewhat smart so they tacked on ware. They following day Rack Middleware was introduced.

Rack Middleware

Middlware sits between a web server and an app and allows developers to manipulate the requests and responses

the two exchange. Middlewares can be chained, each one altering the request/response and passing it along to

the next one in the chain. Rack provides a small Rack::Builder DSL for constructing Rack apps that use

middleware.

app = Proc.new { |env| ['200', {'Content-Type' => 'text/html'}, ['A barebones rack app.']] }

builder = Rack::Builder.new

builder.use FooMiddleware

builder.use BarMiddleware

builder.run app

Rack::Handler::WEBrick.run builder

use adds middleware to the stack. run dispatches to an application.

Rack Middleware must follow the same Rack guidelines with one extra rule - it must have an initialize method

that takes 1 argument, the next thing in the stack built by Rack::Builder. When a request comes in the call

method will be invoked with the request named env. The middleware can then decide to manipulate the request and

pass it down the stack towards the app. It can also manipulate it when the response is passed back up the

stack to it.

Let’s take a look at a basic middleware:

class FooMiddleware

def initialize(app)

@app = app

end

def call(env)

# env represents the request

# @app.call passes the request down the stack to the app

status, headers, body = @app.call(env)

# At this point the response can be manipulated

[status, headers, body]

end

end

That’s really all there is to know about Rack. This little bit of knowledge will prove super useful when working with most Ruby web applications as we’ll see in the next sections.

Flipper::UI

Flipper provides a really slick UI for managing feature flags that can be mounted at any endpoint.

Rails.application.routes.draw do

mount Flipper::UI.app(Flipper) => '/flipper'

end

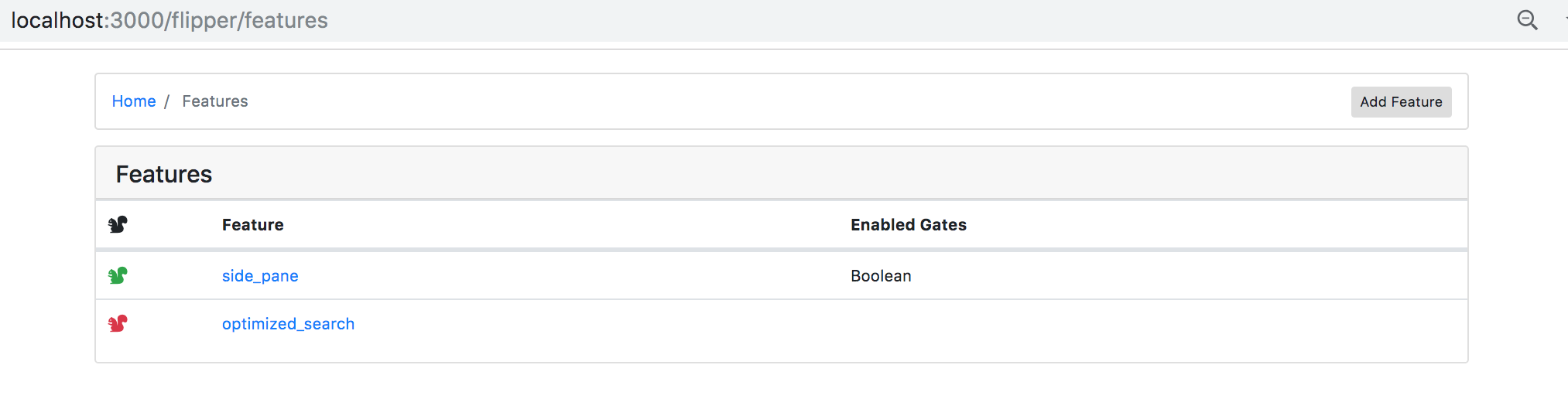

Navigating to /flipper will now display a list of features:

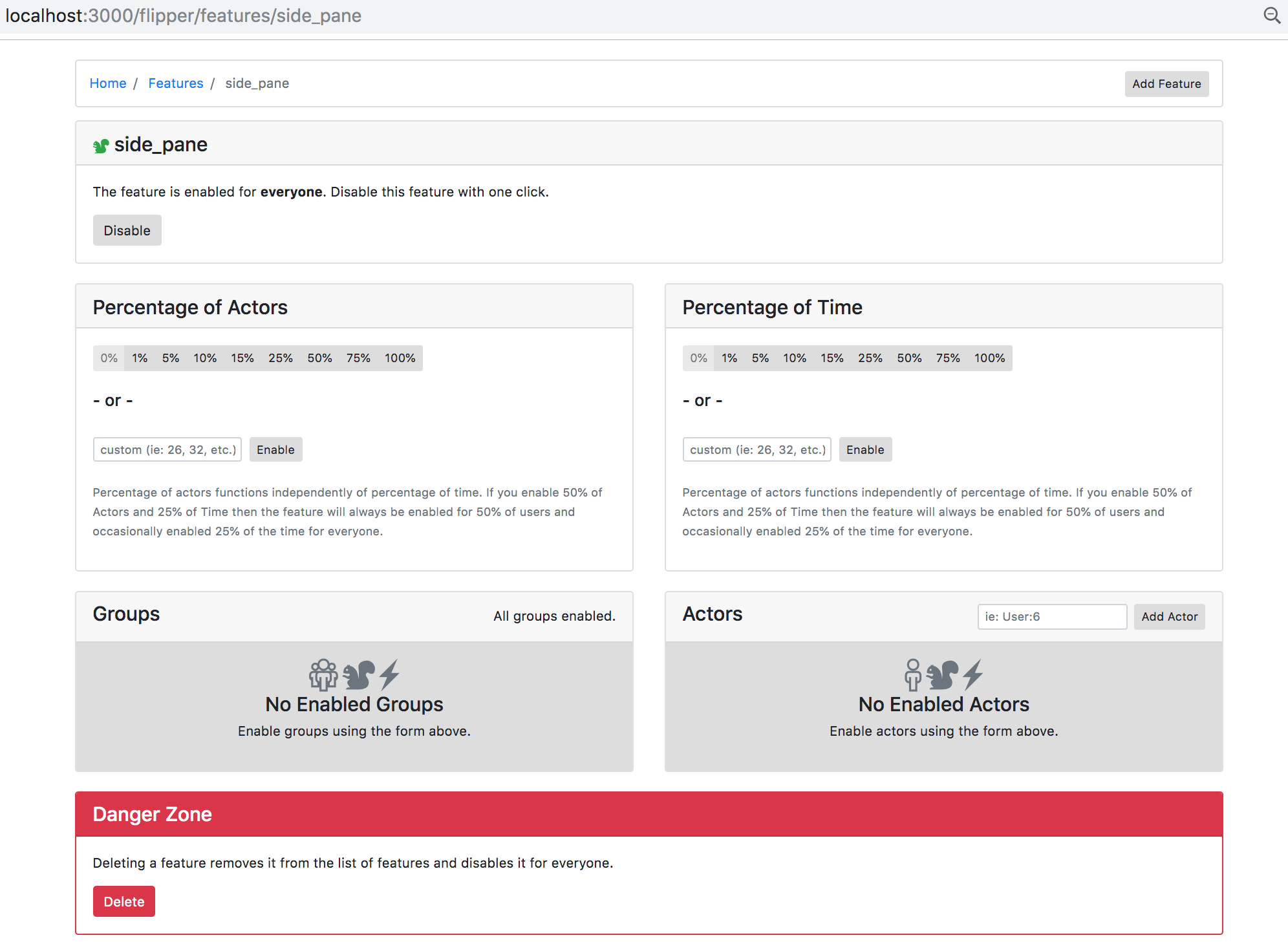

Clicking into one of those features will take users to a page for managing that feature:

With one line of code you can provide users of your library with a really nice web interface thanks to Rack. mount expects a Rack app, which is exactly what Flipper::UI.app returns. Whenever a request hits /flipper we can guarantee that

our app’s call method will be invoked with a Hash representing the request.

Since we all now know how Rack works you will have no problem seeing that Flipper::UI is just a Rack

application built on top of a plain old Ruby lambda:

source

module Flipper

class UI

def self.app(flipper = nil, options = {})

env_key = options.fetch(:env_key, 'flipper')

app = ->() { [200, { 'Content-Type' => 'text/html' }, ['']] }

builder = Rack::Builder.new

yield builder if block_given?

builder.use Rack::Protection

builder.use Rack::Protection::AuthenticityToken

builder.use Rack::MethodOverride

builder.use Flipper::Middleware::SetupEnv, flipper, env_key: env_key

builder.use Flipper::Middleware::Memoizer, env_key: env_key

builder.use Middleware, env_key: env_key

builder.run app

klass = self

builder.define_singleton_method(:inspect) { klass.inspect } # pretty rake routes output

builder

end

end

end

If you look closely you’ll notice one line that opens some pretty cool doors.

def self.app(flipper = nil, options = {})

# env_key = options.fetch(:env_key, 'flipper')

# app = ->() { [200, { 'Content-Type' => 'text/html' }, ['']] }

# builder = Rack::Builder.new

yield builder if block_given?

# builder.use Rack::Protection

# builder.use Rack::Protection::AuthenticityToken

# builder.use Rack::MethodOverride

# builder.use Flipper::Middleware::SetupEnv, flipper, env_key: env_key

# builder.use Flipper::Middleware::Memoizer, env_key: env_key

# builder.use Middleware, env_key: env_key

# builder.run app

# klass = self

# builder.define_singleton_method(:inspect) { klass.inspect } # pretty rake routes output

# builder

end

When provided a block, Flipper::UI.app invokes the block, yielding the Rack::Builder instance. This

exposes the internal Rack::Builder instance allowing developers to chain any additional middleware they’d

like:

Rails.application.routes.draw do

mount Flipper::UI.app(Flipper) { |builder|

builder.use(Middleware)

} => '/flipper'

end

Use Case: Flipper Auditing

At work we needed an audit trail of any changes made through the Flipper UI.

-

Who made the change?

-

Which feature was enabled?

-

What date were they enabled?

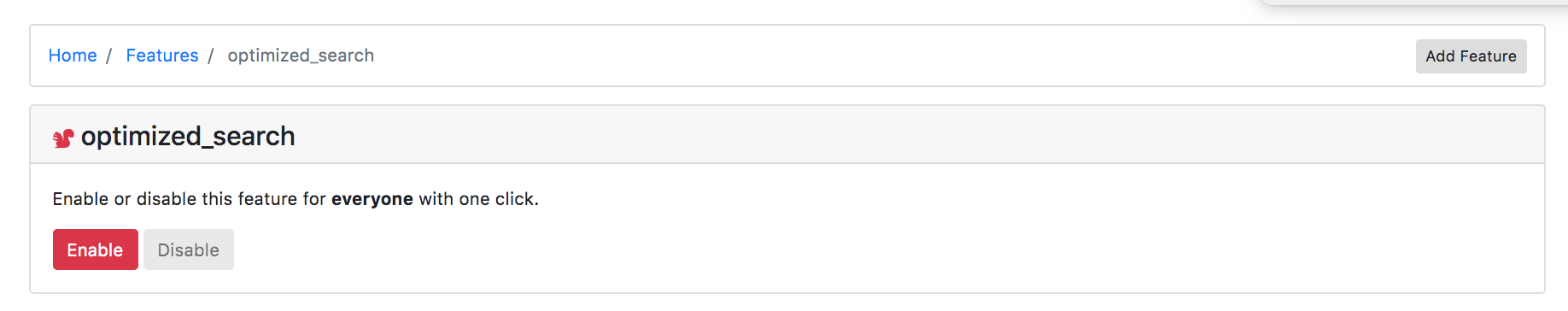

Clicking the Enable button enables a feature for all users:

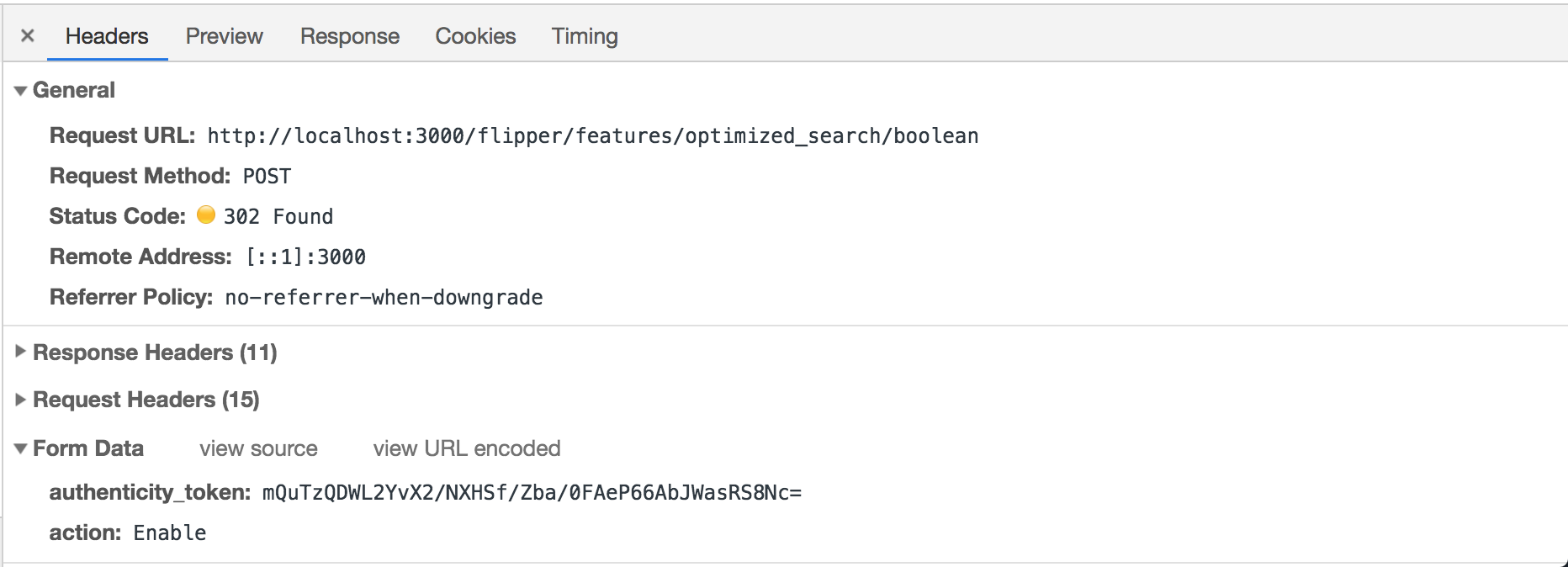

In Chrome’s network inspector we see this button makes a:

- POST request to /flipper/features/feature_name/boolean

- Body includes some form data

{ action: enable, authenticity_token: ***** } - Responds with a 302 HTTP status code (redirect)

We also know we have an authenticated user interacting with the UI so can get the user making these requests from the server. All of this information combined tells us:

Who made the change? - currently signed in user

Which feature was enabled? - /features/optimized_search/boolean

Who was enabled? - /features/optimized_search/boolean; { action: 'Enable' }, in other words

everyone

302 - tells us this request was succesful

Audit Middleware

Let’s implement a simple middleware that simply logs this info.

class FlipperUIMiddleware

def initialize(app)

@app = app

end

def call(env)

status, headers, body = @app.call(env)

request = Rack::Request.new(env)

user_email = env['warden'].user.email

message = format(user_email, request, status)

Rails.logger.info(message) unless asset_request?(request.url)

[status, headers, body]

end

private

def asset_request?(url)

/\.\w+$/.match(url)

end

def format(user_email, request, status)

msg = {

email: user_email,

method: request.request_method,

url: request.url,

params: request.params.except('authenticity_token'),

status: status

}

JSON.generate(msg)

end

end

And make sure Flipper::UI is using it

Rails.application.routes.draw do

mount Flipper::UI.app(Flipper) { |builder|

builder.use(FlipperUIMiddleware)

} => '/flipper'

end

Now all requests made to flipper/ will pass their responses through our middleware.

Some notes on the middleware:

- We’re using a warden-based authentication framework, Devise, which uses its own middleware to add the current user to the request

Rack::Requestjust provides a simple interface for interacting with the request.- We only log requests triggered by the user. Since all requests to flipper/ will pass through this middleware we need to filter out any requests for asset files (files ending in .css, .js, .png, etc.). /.\w+$/.match(url) takes care of this.

- We filter our the authenticity_token, which is there to protect against CSRF attacks.

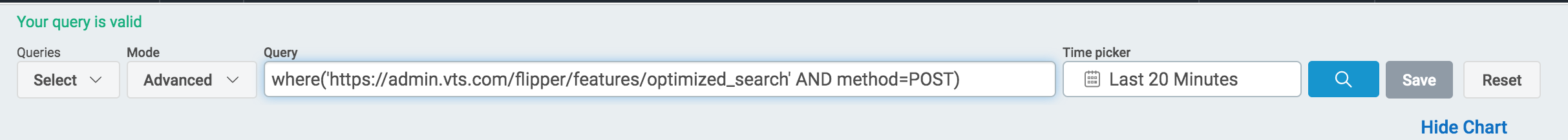

Now in our logs we can easily query for the these messages and get an understanding of who’s done what within the Flipper UI.

Logentries’ advanced LEQL

Logentries’ advanced LEQL

I always find it useful connecting the theory with real-world examples. Hopefully this gives you just a bit more understanding of your Rack applications.